Автор: Adam B. Vary

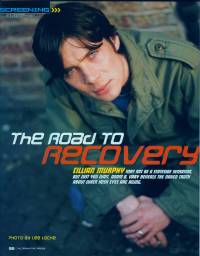

Cillian Murphy may not be a stateside sensation, but you just wait. Adam B. Vary reveals the naked truth about when Irish eyes are riling.

The first good look most Americans will get at Cillian (pronounced "Kil-ee-an") Murphy will leave little to the imagination. He's naked—we're talking spread-eagle, let's-see-what-you've-got, full-Monty nude. What's more, Murphy says, he's "not too bothered about it."

Maybe some background is in order: The birthday-suit scene in question is from 28 Days Later..., a modern-day spin on the zombie genre that scared the kidney pie out of Britain last fall and is due for U.S. release June 27. In it, Murphy plays Jim, a London bike messenger who wakes up, naked, in an abandoned hospital, and discovers he must contend with an England evacuated of virtually every living soul. That is, except for the "infecteds"—bloodthirsty, brutal automata carrying a fast-acting blood-borne virus that makes its victims content only to kill, and kill often. (The title refers to the chronological jump the film makes from the botched laboratory raid that releases the virus to Murphy's alfresco awakening.)

It is, pardon the pun, a killer premise, and Murphy is clear that his character's declothed debut is a perfect fit. "It made complete sense to me," he says. "I think it's a very arresting image to be greeted with when you meet the protagonist of a film... I wanted to try [to] give an image of a child or somebody completely without any resources, really completely abandoned."

Born in Cork, Ireland, the lanky, finely featured actor has had better luck. A year and a half into a law degree, he landed his first acting gig at 19 with a why-not audition for a local play called Disco Pigs, about a boy and a girl so close they create their own language. The play's big-screen adaptation caught the eye of British director Danny Boyle (Trainspotting, The Beach), who asked Murphy to read for 28 Days Later...; and, two more auditions later, Murphy found himself before Boyle's digital-video camera with mobs of red-eyed infecteds bucking the zombie creep. "[Boyle] cast athletes [as the zombies], so ... they had these guys fucking bootin' it toward you," Murphy recalls. "It does become terrifying."

Murphy says it was most unnerving, however, filming the jaw-dropping five-minute sequence in which his character stumbles around utterly empty London landmarks like the London Bridge and Piccadilly Circus. "You so associate [London] with bustle and rush and chaos and just this heave of people," he says. "I'd walked down all those streets every day—its's weird, seeing all those landmarks just desolate." Desolate to a degree, anyway. "It was very much guerilla filmmaking," Murphy says with a fond glint to his south-Irish brogue. "[We would] have about five minutes [per location] to catch every bit... At the corner of the edge of the frame, there's people screaming to get to work."

The four-day July shoot was so grueling that the production took a month-long break, resuming photography on September 1, 2001. Ten days later, as Murphy puts it, "events overtook the film." The timing is peculiar, an apocalyptic film—about a virus called "Rage"—hitting theaters amid a global war against terror. Murphy can understand the ambiguity.

"[Immediately after 9/11], part of you was going, 'Oh, my God, we're just making a stupid film, [when] horrendous events have taken place and the world is in chaos and all.' But then, there's a part of you that says also, 'We're making a film that reflects this [feeling] as well, or, I think, comments on it in some way.' I definitely think [the film] does say something to Americans now, about paranoia and the feeling that we're all vulnerable nowadays. You've got to comment on that."

|